Cycle-delic sounds.

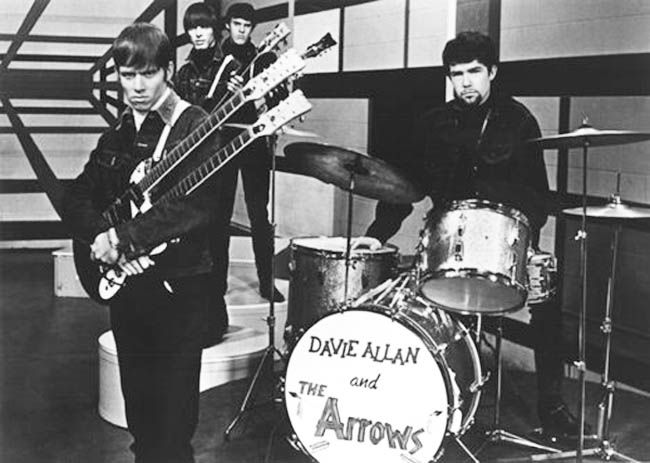

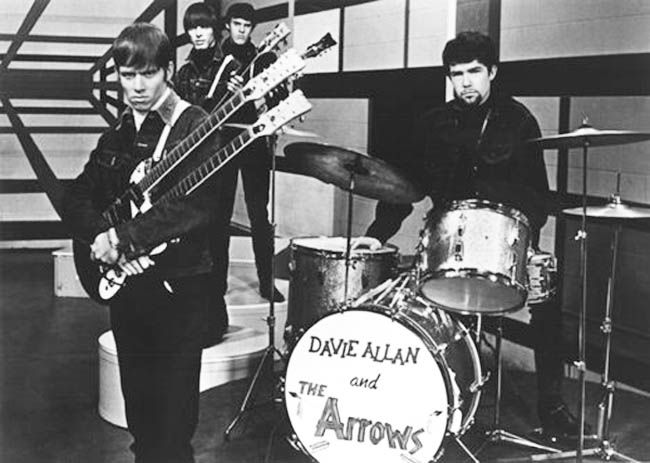

A few years ago, I posted something on here about Davie Allan And The Arrows, in which I compared and contrasted Davie Allan to Dick Dale, and called him King Of The Motorcycle Guitar. Don't get me wrong, I stand by that completely, but I've recently learned that I didn't know the extent of Davie Allan's awesomeness back when I wrote that post. It's because I took the lazy way out, really--I had downloaded the 40-song double disc anthology of his work, "Devil's Rumble," and then discovered that the anthology would fit on a single burned CD-R if I cut one song from it. That song, "Cycle-delic," was 7 minutes long, over twice the length of anything else on that compilation. I should have known that it was something special based on that alone. But instead, my desire to save CD-R space won out, and I burned "Devil's Rumble" minus "Cycle-delic" to one disc.

Fastforward to sometime in the past 12 months or so. The record store near where I work, having read the writing on the wall where CDs are concerned, has really stepped up their selection of new vinyl, including quite a few awesome garage rock reissues. I discover a brand-new shrinkwrapped reissue of Davie Allan's classic 1968 LP "The Cycle-delic Sounds Of Davie Allan And The Arrows." I can't resist. I spend the $16 they want for it, and I bring it home. There, I finally learn of my much earlier mistake where the song "Cycle-delic" is concerned.

The first song on the album is "Cycle-delic," that song I spurned before due to time constraints. Literally every song on "Cycle-delic Sounds" was eventually collected on "Devil's Rumble," so at this point, "Cycle-delic" itself is the only song on the LP that I don't know intimately. It jumps out at me, the second I put the album on, as a revelation. It's been a good year or so since then, though, and even though I now know it just as intimately as I know the entire rest of the album, it still stands out to me. This 7-minute epic is without a doubt Davie Allan's magnum opus, containing not only the most extreme fuzz solos he ever laid down but also the most dramatic deviation from his typical song construction formula.

First of all, rather than featuring the sorts of verses and choruses that typically alternate on an Arrows track, "Cycle-delic" is based around a simple, repetitive riff that the rhythm section keeps playing throughout most of the song. Its minimal chord changes and unceasing pulse presage Krautrock in some ways, though there's still plenty of the surf-guitar instrumental foundation that connects it back to more typical Arrows work. Within 15 seconds or so, after a few brief repetitions of the song's base riff, Davie Allan launches off into the ether. He's both overdriving his amp to a ridiculous extent and manipulating the hell out of a wah-wah pedal, combining the two sonic manipulations to make his guitar sound like it is both on fire and screaming for its life. This first solo lasts until about 1:30, at which point it is joined by a free jazz saxophone that would sound right at home on John Coltrane's "Ascension" LP. Allan keeps soloing behind it, and when it drops out after 30 seconds or so, he goes into even more extreme guitar destruction, culminating in a passage, at about 2:45, where it sounds like he's yelling into his pickups. If that's what he's doing, he's frantically working his wah-wah pedal at the same time, so whatever vocalizations he's delivering are completely incoherent, but that just makes the whole thing even cooler.

Finally, the rhythm section drops back into a vamp, and while the drummer keeps time with his kick pedal, a harmonica solo begins. Allan just feeds back aimlessly at the beginning of this solo, but after a couple of measures, he and the harmonica player begin exchanging phrases, Robert Plant/Jimmy Page style. Davie tires of this quickly, though, and slamming his wah-wah pedal back down, he takes the song over once again. The rhythm section, presumably led by excellent rhythm guitarist/songwriter Mike Curb (though I'm actually guessing at this, since individual credits are absent from "Cycle-delic Sounds"), follows Davie's lead, and back into the frantic, pounding pulse we go, carried by sheets of guitar noise and crackling tambourines.

This whole thing still isn't over, though, and at about 4:25, the first real change in the main riff occurs, as the Arrows switch into a start-stop chug riff that builds to a crescendo before dropping down into a much quieter repetition of the original riff. Finally, at maybe 5:20 or so, the rhythm section drops out completely, except for the periodic ringing chime of what might be a triangle or a bell of some sort. Davie quit soloing and dropped out of the mix completely at about the point when the band got quiet, but now, as they cut out, he comes back in. There's no real rhyme or reason to what he's doing by now, his sinister, howling sheets of fuzz noise having lost all connection to the rest of the song some time back, and he finally quits playing completely at the same time that the rhythm section drops out. Now all that's left other than that repeated chiming sound is Mike Curb, playing a gorgeous melodic arpeggio all by himself.

This is perhaps the most striking portion of the entire song, representing as it does a complete departure from the normal working methods of Davie Allan And The Arrows. Never before have they left behind their driving, fast-paced rhythms. Never before have they opened a song up as widely as this. The effect is panoramic, as if the camera has just pulled back from a closeup shot of some speeding biker on a mountain road to a much wider angle that shows the entire landscape, and how comparatively tiny the biker is within it. The fact that this sudden departure from the norm works so incredibly well, indeed takes my breath away every time I hear it, is a testament to the talents of Davie Allan and the rest of the Arrows. A few seconds after this dropout, Davie adds a fuzzier harmonizing arpeggio to what his rhythm guitarist is playing, and soon he's brought the rest of the band back in for a quickly building crescendo that caps off the entire amazing song. I never tire of hearing it, and in fact, I've played it through at least a dozen times while writing this entry.

Davie Allan And The Arrows - "Cycle-delic"

That link also contains Davie's most famous single, "Blue's Theme," just so you can hear the difference between "Cycle-delic" and his usual work. Of course, you can also do that at the above video clip, the opening credit sequence of "The Wild Angels," over which "Blue's Theme" plays. The character Peter Fonda plays in "Wild Angels" is named Blue, so it's an appropriate time in the film for that song to play. By the way, any of you who haven't seen "The Wild Angels" should really go hunt it down.

One more thing: Davie Allan is still performing and recording music to this day, which is something I didn't know until googling him while writing this entry. His website is davieallan.com, and he'd love to sell you copies of "Cycle-Delic Sounds" as well as many other releases that he's done over the years. Most CDs are $12.50 postpaid from his website, which is quite reasonable, so hit him up, why don't you? I can assure you that I will, as soon as I can afford to. After all, there's a lot more where this came from.

Fastforward to sometime in the past 12 months or so. The record store near where I work, having read the writing on the wall where CDs are concerned, has really stepped up their selection of new vinyl, including quite a few awesome garage rock reissues. I discover a brand-new shrinkwrapped reissue of Davie Allan's classic 1968 LP "The Cycle-delic Sounds Of Davie Allan And The Arrows." I can't resist. I spend the $16 they want for it, and I bring it home. There, I finally learn of my much earlier mistake where the song "Cycle-delic" is concerned.

The first song on the album is "Cycle-delic," that song I spurned before due to time constraints. Literally every song on "Cycle-delic Sounds" was eventually collected on "Devil's Rumble," so at this point, "Cycle-delic" itself is the only song on the LP that I don't know intimately. It jumps out at me, the second I put the album on, as a revelation. It's been a good year or so since then, though, and even though I now know it just as intimately as I know the entire rest of the album, it still stands out to me. This 7-minute epic is without a doubt Davie Allan's magnum opus, containing not only the most extreme fuzz solos he ever laid down but also the most dramatic deviation from his typical song construction formula.

First of all, rather than featuring the sorts of verses and choruses that typically alternate on an Arrows track, "Cycle-delic" is based around a simple, repetitive riff that the rhythm section keeps playing throughout most of the song. Its minimal chord changes and unceasing pulse presage Krautrock in some ways, though there's still plenty of the surf-guitar instrumental foundation that connects it back to more typical Arrows work. Within 15 seconds or so, after a few brief repetitions of the song's base riff, Davie Allan launches off into the ether. He's both overdriving his amp to a ridiculous extent and manipulating the hell out of a wah-wah pedal, combining the two sonic manipulations to make his guitar sound like it is both on fire and screaming for its life. This first solo lasts until about 1:30, at which point it is joined by a free jazz saxophone that would sound right at home on John Coltrane's "Ascension" LP. Allan keeps soloing behind it, and when it drops out after 30 seconds or so, he goes into even more extreme guitar destruction, culminating in a passage, at about 2:45, where it sounds like he's yelling into his pickups. If that's what he's doing, he's frantically working his wah-wah pedal at the same time, so whatever vocalizations he's delivering are completely incoherent, but that just makes the whole thing even cooler.

Finally, the rhythm section drops back into a vamp, and while the drummer keeps time with his kick pedal, a harmonica solo begins. Allan just feeds back aimlessly at the beginning of this solo, but after a couple of measures, he and the harmonica player begin exchanging phrases, Robert Plant/Jimmy Page style. Davie tires of this quickly, though, and slamming his wah-wah pedal back down, he takes the song over once again. The rhythm section, presumably led by excellent rhythm guitarist/songwriter Mike Curb (though I'm actually guessing at this, since individual credits are absent from "Cycle-delic Sounds"), follows Davie's lead, and back into the frantic, pounding pulse we go, carried by sheets of guitar noise and crackling tambourines.

This whole thing still isn't over, though, and at about 4:25, the first real change in the main riff occurs, as the Arrows switch into a start-stop chug riff that builds to a crescendo before dropping down into a much quieter repetition of the original riff. Finally, at maybe 5:20 or so, the rhythm section drops out completely, except for the periodic ringing chime of what might be a triangle or a bell of some sort. Davie quit soloing and dropped out of the mix completely at about the point when the band got quiet, but now, as they cut out, he comes back in. There's no real rhyme or reason to what he's doing by now, his sinister, howling sheets of fuzz noise having lost all connection to the rest of the song some time back, and he finally quits playing completely at the same time that the rhythm section drops out. Now all that's left other than that repeated chiming sound is Mike Curb, playing a gorgeous melodic arpeggio all by himself.

This is perhaps the most striking portion of the entire song, representing as it does a complete departure from the normal working methods of Davie Allan And The Arrows. Never before have they left behind their driving, fast-paced rhythms. Never before have they opened a song up as widely as this. The effect is panoramic, as if the camera has just pulled back from a closeup shot of some speeding biker on a mountain road to a much wider angle that shows the entire landscape, and how comparatively tiny the biker is within it. The fact that this sudden departure from the norm works so incredibly well, indeed takes my breath away every time I hear it, is a testament to the talents of Davie Allan and the rest of the Arrows. A few seconds after this dropout, Davie adds a fuzzier harmonizing arpeggio to what his rhythm guitarist is playing, and soon he's brought the rest of the band back in for a quickly building crescendo that caps off the entire amazing song. I never tire of hearing it, and in fact, I've played it through at least a dozen times while writing this entry.

Davie Allan And The Arrows - "Cycle-delic"

That link also contains Davie's most famous single, "Blue's Theme," just so you can hear the difference between "Cycle-delic" and his usual work. Of course, you can also do that at the above video clip, the opening credit sequence of "The Wild Angels," over which "Blue's Theme" plays. The character Peter Fonda plays in "Wild Angels" is named Blue, so it's an appropriate time in the film for that song to play. By the way, any of you who haven't seen "The Wild Angels" should really go hunt it down.

One more thing: Davie Allan is still performing and recording music to this day, which is something I didn't know until googling him while writing this entry. His website is davieallan.com, and he'd love to sell you copies of "Cycle-Delic Sounds" as well as many other releases that he's done over the years. Most CDs are $12.50 postpaid from his website, which is quite reasonable, so hit him up, why don't you? I can assure you that I will, as soon as I can afford to. After all, there's a lot more where this came from.

Labels: Music